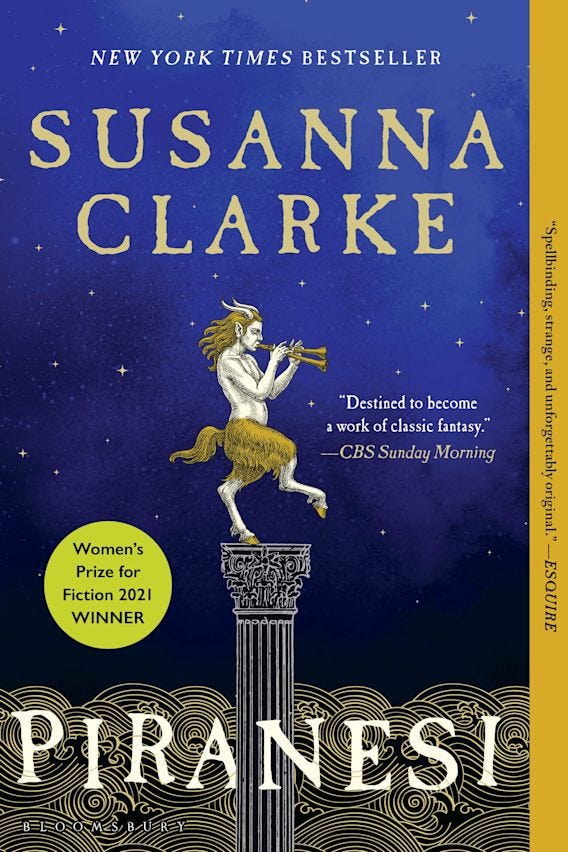

Identity & Spaces: On Susanna Clarke's 'Piranesi'

Spoiler-free remarks on a Damn-Good Fantasy Novel

Author’s Note: This piece was originally supposed to be finished and published a few months ago when I had finished the novel. I did not write it all out then and so this should not be considered a definitive discourse on my impressions of the work. Regardless, I will endeavour to recall my impressions as they have developed since then and to give some voice to the virtues of the novel.

The world inhabited by the protagonist of Susanna Clarke's 2020 fantasy thriller is a liminal delicacy. In endless winding hallways and alcoves littered with statues and vast rooms, the habitat of the novel is an ecosystem complete with inclement weather patterns and a battering sea that together build an austere and moody background for the narrative to play upon. It is immersed in this baroque wasteland that the protagonist, Piranesi, has developed their identity: a face that changes significantly (if subtly) throughout the novel.

I enjoyed Piranesi, selfishly and terribly, I enjoyed it. The first half of the novel was a gradual experience, a meditation. The second half was a crisis I chewed at for only three hours (such is the twist of the middle act: it inspires voracious reading). I was moved by the narrative and by the development of the protagonist and their perception of the events unfolding at them. The tale is a true classic in both the fantastical sense of the Other World so common in fantasy, but also in the ultimate path of the plot. This latter aspect I will not discuss much more; go and read it and then you will know. What the novel accomplishes in its world and character is an expression of identity and space that leaves one desolate, though hopeful.

Piranesi is a great intellect trapped in a great world, an elusive world that they study meticulously and record in great depth. Their records span a berth of curiosities found throughout the immense halls and hollows of their dwelling, a place they graciously refer to as the House. At the start of the novel, Piranesi is a self-described Child of the House. Their sense of self is tied inextricably to the whim of the world's strange nature: the House provides and they move in turn with its providence. Like a sage, things come to them and they accept them. They do not question the will of the house and do not consider any reason for the phenomena of the house beyond its Will. Yet, Piranesi is a scientist and even in their ecclesiasticism for this domain there is a cold logic that defines their spirituality. Piranesi understands their world with intellectual reverence such that they do not seek to know so much as they seek to know their self through knowing the House. This ends up forming the plot of the novel, as Piranesi recognizes that their memories of arriving at the House have been tampered with by a mysterious visitor.

The slow epiphany of the novel is too well executed to reveal; I cannot bear to spoil it. It is a slow-burning twist that seizes the reader despite their foresight. Even if you know what is happening, the outcome is arresting in its emotional depth. It is an inversion that rewrites the whole novel in a new tone and brings the reader closer to Piranesi and the world he occupies. It is a breakdown of identity that happens before the reader’s eyes: tragic, ephemeral, and beautiful. This is the power of Piranesi. It confounds us, then compels us to a truth we know is a lie, and then reveals that lie all as a journey we experience with the protagonist, Piranesi. It is a powerful novel about identity, truth, and the liminal nature of experiencing change. It recalls to us in the embodiment of the House that there is no hope in Knowing. We may seek to know but we may never encompass Knowing—there will always be another layer of perception. This is ultimately applied to identity as Piranesi’s character develops throughout the novel, then it is applied to the World1. We may presume to understand, but then we find out through happenstance that we don’t understand as much as we thought we did2. By the end, do we ever really know anything? Or are we just a process of knowing and un-knowing—ecstatic verbs ever-changing tense and meaning?

Piranesi implies such questions, and so do I, often. Thus, I highly recommend it as a fantasy novel if the Reader is interested in a beautiful story about identity and the spaces, both internal and external, where we may know ourselves. As an epistolary novel, it excels in the highest order. As an Otherworld fantasy, it is a delight of worldbuilding and mystery. As a novel, it is worth your while. Now, go and read.

I will note additionally that I was struck throughout my reading by an awareness of the publication coinciding with the pandemic and how the liminality of Piranesi’s world recalled to me the ennui of COVID. There is a haunting quality to the novel that continually compresses the world as the plot funnels to the conclusion. Then, it is over. Suddenly, we are finished, and we cannot be the same. I don’t believe Clarke wrote the novel or the story with this in mind (the novel was published in 2020), but it hung over my reading like a pale spectre. Perhaps this is because my overall experience through the pandemic was traumatic, and I do not feel the same afterwards as I did before. But that is for another post.

I hope you enjoyed this one. Thank you for reading3.

This latter aspect of the novel has been compared to the allegory of the cave by other commentators.

See, we always forget about the things we don’t know we don’t know.

And thank you to my brother for buying me Piranesi. Good call.